The stethoscope is a simple tool using basic physics to amplify noise within the body. You’ve probably seen one by now or even better, your chest or your back made contact with one during one of your visits to your medical practitioner. It is a very common occurrence.

The word stethoscope is derived from the two Greek words, stethos (chest) and scopos (examination). Apart from listening to the heart and chest sounds, it is also used to hear bowel sounds and blood flow noises in arteries and veins.

History of the stethoscope

In the early 1800’s, and prior to the development of the stethoscope, physicians would often perform physical examinations using techniques such as percussion (tapping) and immediate auscultation (listening). In immediate auscultation, physicians placed their ear directly on the patient to hear internal sounds.

This technique suffered from several drawbacks, the foremost being that it required physical contact between the physician and the patient (putting an ear on a woman’s chest…) and proper placement of the ear. In addition, the sounds observed by the physician were not amplified in any way, creating the possibility of missing key sounds that might indicate potential illness. Finally, the act of performing immediate auscultation could be awkward for both the physician and patient, especially female patients.

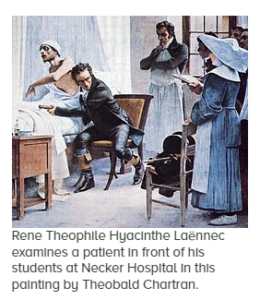

To avoid this awkwardness, a French doctor named Rene Laennec created the first version of the stethoscope by rolling up a paper tube and using it as a funnel. Not only did this solve the problem, but Dr. Laennec realized that it amplified the sounds in the woman’s chest. He is the one credited with the naming of this device “the stethoscope”.

Doctors would use this version of the stethoscope for 25 years before and Irish physician named Arthur Leared created a more complex model with two earpieces (called binaural) on the ends of stiff metal tubes. George P. Camman in New York then began widely selling this version. But it was heavy and impractical.

At first, the medical community did not want to use the model with two earpieces because they were unsure if the two earpieces would produce consistent results. Eventually, however, the newer type became widely accepted until, a hundred years later, another inventor made improvements to this design.

The Scottish doctor Somerville Scott Allison designed a similar instrument called a “stethophone” that used two “bells” (or the part of the stethoscope that the doctor presses against a patient’s body) to listen to different parts of the body at the same time, such as the heart and the lungs.

By the 1940s, the most common style of stethoscope included these two different bells connected to two large, rubber tubes that then attached to metal ear tubes. This design was heavy and difficult to carry around, but it was not until the 1960s that a lighter model would come around.

In 1961, Harvard Medical School professor and cardiologist Dr. David Littmann described what he wanted in an ideal stethoscope in the American Medical Association journal. He described a device with an open chest piece for low-pitched sounds, a closed piece for higher pitched sounds, firm tubing in the “shortest length possible,” a spring to hold the earpieces together when they are not in use, and for the device to be lightweight.

Littmann was successful in creating his vision. Modern day stethoscopes can listen to lower or higher pitched noises by adjusting the pressure of the bell against the patient’s body. Today, nurses and doctors around the world use Littmann’s design and his brand is one of the most popular in the world.

What Is your doctor listening for?

As part of a physical exam, your doctor will listen to your lungs for various sounds. If you have pneumonia, your lungs may make crackling, bubbling and rumbling sounds when you inhale. If your healthcare provider hears a crackling noise that sounds a bit like velcro, they might run more tests to determine if you have pulmonary fibrosis. A patient with asthma will produce a wheezing sound upon auscultation of the lungs. These are just a few examples. The doctors listen to your heart as well.

Stethoscope, a relic of medicine?

In recent years there have been calls for doctors to ditch the stethoscope and adopt high-tech devices.

Most of the doctors now call the stethoscope a “relic,” noting that miniaturized ultrasound scanners – not much bigger than a deck of cards – can now provide detailed images of the heart, rendering the stethoscope obsolete. Other devices that connect to smartphones can amplify heartbeats, help with diagnosis, and the data can be sent wirelessly to patients’ electronic medical records.

A U.S. study conducted two years ago compared hand-held ultrasound devices with physical examination (stethoscope). It found that ultrasound devices correctly identified 82 per cent of patients with heart abnormalities while a physical exam (with a stethoscope) had a 47-per-cent rate of successful identification.

So, is it time to put the stethoscope in the closet of medicine? Not so fast, say some…

These are still several examples where the old-fashioned stethoscope is more than sufficient to do the job:

- Assessing pregnant women who are short of breath: These patients usually don’t like getting chest X-rays or CT scans. A stethoscope can help determine if their breathing difficulties are caused by things like a flare-up of asthma or pneumonia because the sounds vary with the condition, without exposing the patient to any radiation.

- Declaring a patient dead: Death is not like in the movies – “there is not necessarily a death rattle.” In fact, sometimes it is not obvious the patient has passed away, especially when there’s been a slow steady decline. “The body is still warm and your eyes can play tricks on you as to whether there is any respiratory movement,” doctors say. The stethoscope can provide an answer. “You lay the stethoscope on the chest and it is absolutely silent. The patient has expired. “Conversely, if there is the occasional thump, thump, thump going on” then the patient is still alive.

- Checking heart rate: Many patients have a heart rate that’s too fast – sometimes exceeding 160 beats per minute. Doctors will often prescribe medications like beta-blockers to bring the heart rate down to a more normal range of 60 beats. But checking the heart rate by putting two fingers on the wrist can sometimes give a misleading measurement because not every pulse can be felt with this approach. However, if the stethoscope is placed on the chest at the same time, it’s obvious when a heartbeat is not getting through to the wrist.

- Measuring blood pressure: There are now many electronic devices that automatically measure blood pressure. But they sometime get out of whack or break down. The stethoscope, combined with a sphygmomanometer (inflatable cuff), is a handy backup when the electronic devices crash.

- Detecting heart problems: Before starting an operation, doctors usually want to know if a patient has a pre-existing heart problem that could lead to surgical complications. A definitive diagnosis can be made with an echocardiogram test. But it takes time to order the test and do it. By contrast, the stethoscope can help quickly identify cardiac conditions in patients in need of urgent surgery, such as a senior who has fallen and broken a hip.

- Gauging recovery from surgery: The anesthetic used in surgery tends to slow down the bowels. Many patients have no appetite and may be nauseous when they wake up after an operation. By using a stethoscope to listen to the belly, the doctor can often get an indication of the patient’s stage of recovery. “When bowel sounds have come back…it can be a sign that the patient is turning the corner.”

Medicine’s most important symbols are the white coat and the stethoscope. These are symbols of status after all.

At a time when new diagnostic technologies (X-rays, ultrasounds, MRI’s, CT scans etc.) threaten to render the stethoscope obsolete, doctors are shown to want to retain the stethoscope as a symbol of the skill and knowledge they possess.